Bursitis, stress fractures and cartilage tears

With Mr Arjuna Imbuldeniya, Consultant Hip, Knee & Trauma Surgeon

Hip pain: diagnosing and managing your running injury

Posted on Wed May 1, 2019

Mr Arjuna Imbuldeniya, Consultant Hip, Knee and Trauma Surgeon, explores some of the most common problems leading to hip pain in runners, and explains the best ways in which we can work together to manage them.

Despite some showers on Sunday, 23rd April 2023, a record number of participants – over 48,000 – buoyed up by cheerful supporters, came together on the capital’s streets for the London Marathon.

Whether planning to smash a PB or simply trying to cross the finish line, people were training intensely over the last few months in preparation for the monumental event.

But what can we do for those who hit a stumbling block in the form of hip pain associated with their running?

Hip pain: bursitis

Causes

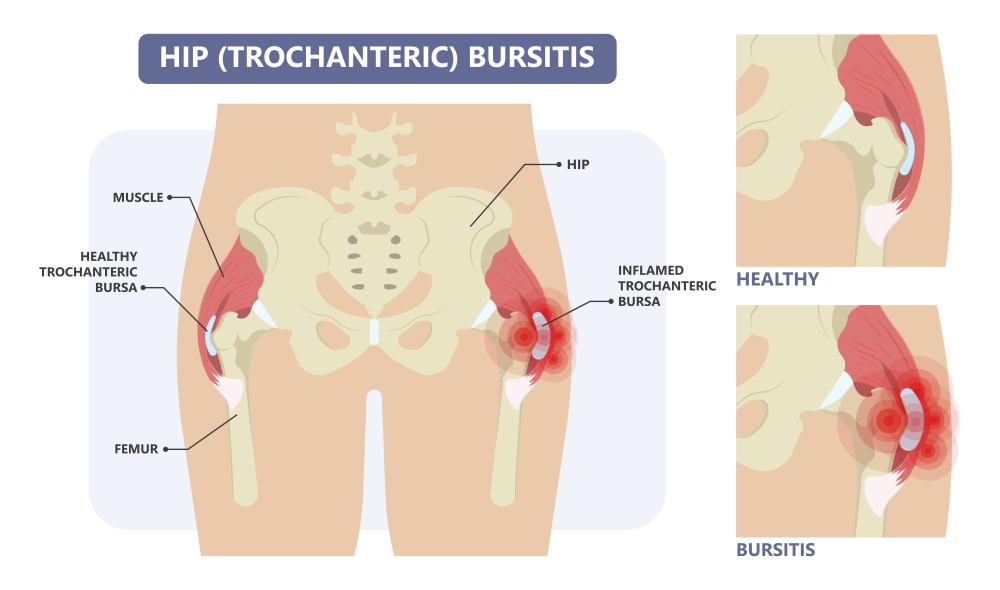

There are several bursae – small, fluid-filled sacs that cushion the bones, tendons and muscles near joints – around the hip (the gluteus medius, iliopsoas, ischial and trochanteric bursae). By far the most common form of hip bursitis – when bursae become inflamed – is trochanteric bursitis.

Trochanteric bursitis is a frequently-overlooked cause of hip pain in young adults – particularly in runners – which can be caused either by trauma (for example a fall directly on to the lateral hip) or by the repetitive friction occurring during running.

Patients who overpronate (when the foot rolls too far inward towards the arch) are more likely to develop trochanteric bursitis, as their gait involves inward turning of the knee and in turn an increased angle at the hip, whilst weakness of the hip girdle muscles can also be an exacerbating factor.

Trochanteric bursitis (Sport Doctor London)

Clinical indications

Runners typically present with pain and tenderness over the lateral aspect of their hip and buttock, and report pain whilst lying on the affected side in bed and which is exacerbated by rising from a seated position or whilst climbing stairs.

Diagnosis

X-rays can be useful in the early investigation of those with likely trochanteric bursitis to help exclude the presence of a bony spur which may have triggered the inflammation, but in general, initial management involves taking anti-inflammatory medication, topical ice application and resting the area until the inflammation has resolved.

The condition is usually self-limiting, although it takes at least 2-3 months to heal.

Treatment and management

In addition to routine stretching and strengthening exercises, a good physiotherapy regimen will be able to target any existing muscle imbalances which have contributed to the development of bursitis, although this should be built up slowly to allow the inflammation to settle. Referral to an orthotist may also be beneficial for those with poor foot biomechanics as a contributory factor.

However, if you need to get back to high levels of activity quickly, or symptoms have not improved with more conservative measures, see an orthopaedic specialist for consideration of further imaging modalities (MRI) to help confirm the diagnosis, or for targeted injection therapy to manage the symptoms.

If a bony spur has been identified, the opinion of an orthopaedic surgeon should also be sought as surgical intervention may be required.

Injection therapy

Injection therapy comprises different treatments options which can be injected directly into the affected bursa. Most commonly used – and recommended by The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) – are corticosteroids, which act within a few days to reduce inflammation and have been proven through numerous randomised control trials to improve clinical outcomes for many in the short term (around 3 months).

This provides symptomatic relief and can also enable patients to progress further with strengthening exercises. However, the evidence suggests that the effect is short-lived, and because of the risk of tendon weakness associated with repeated steroid injection, it is recommended that you have a maximum of 3 injections into one area, at least 6 weeks apart. This means that if the trochanteric bursitis has not resolved after this, other options may need to be considered.

Platelet-rich plasma

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is a newer addition in the management of trochanteric bursitis. This technique involves drawing blood from the patient and spinning it in a centrifuge to obtain a sample of plasma with high concentrations (5-10 times the usual level) of platelets, desirable for their high concentration of growth factors which may help to stimulate repair.

This PRP is then injected directly into the affected area – activated platelets release bioactive proteins which recruit other repair factors, stimulate them to repair damaged tissue and promote angiogenesis. The entire healing process in PRP treatment is around 6 weeks, although some require a repeat injection at around 4 weeks.

Because it is a newer technology, research is still ongoing to determine the true effectiveness of PRP for trochanteric bursitis; current results are equivocal. However, many attest to its success.

Should you fail to improve after trying all management options discussed above, you may be suitable for open surgical debridement of the inflamed bursa by an orthopaedic surgeon.

Hip pain: stress fractures

Causes

Stress fractures are relatively common in runners and joggers, and usually involve the metatarsals (five long bones in the middle foot) or tibia (shin bone). They are caused by the repetitive loading of the feet and legs during running, of which various styles can play a contributing role – for example, over-striding with a definite heel-strike may increase your chances of a tibial stress fracture whilst running with a forefoot-strike can overload the foot and lead to metatarsal stress fractures. Diagnosis is by x-ray, DEXA bone scan or MRI.

Alterations in nutrition, running style and work on rebalancing muscles to improve biomechanics can all play their role in preventing further stress fractures, but, once affected, an individual’s only choice is complete rest for around 6-8 weeks whilst the fracture heals, aided by analgesia, ice and splinting if required.

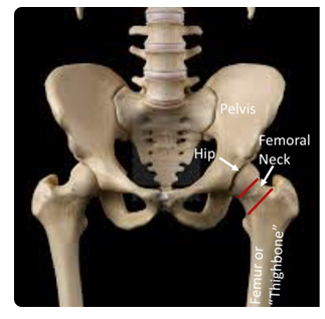

However, one important case to consider in terms of stress fractures in runners where prompt diagnosis is key, is the femoral neck stress fracture.

Femoral neck (Orthopaedic Trauma Association)

Femoral neck

Stress fractures of the femoral neck are, by contrast to those in the lower legs and feet, relatively uncommon (accounting for around 1% of all stress fractures), but occur more often in runners than other groups due to repetitive loading of the femoral neck.

Types of femoral neck fracture (joint-surgeon.com)

This injury should therefore be considered a likely possibility in athletes who present with insidious onset (gradually, with no obvious symptoms) of exertional groin or anterior (near the front) thigh pain and pain at the extremes of movement during examination.

Patients often provide a history of an increase in training intensity or overuse, and describe the pain as worse during high-impact activities and best following periods of activity cessation.

Fractures can occur either on the inferomedial (below and in the middle) femoral neck at the site of compressive stress or on the superolateral (above and towards the side) neck at the site of tensile stress during weight-bearing. Repetitive loading of the femoral neck leads to microscopic fracture formation (known as ‘crack initiation’), whilst continued loading stresses do not permit a healing response to occur and instead lead to ‘crack propagation’.

Clinical indications

The clinical signs and symptoms are non-specific, and diagnosis is further complicated by initial radiographs often appearing normal.

The major concern with delayed diagnosis in these injuries is the potential for the fracture to displace, which significantly worsens outcomes for the patient and leads to a reduction in activity levels along with a 30% risk of avascular necrosis (death of bone tissue due to inadequate blood supply) – elite athletes will not be able to return to their prior level of function should they sustain a displaced fracture.

Therefore, prompt diagnosis and management are key to maintaining activity levels and optimising outcomes.

Diagnosis

The imaging modality for diagnosis is MRI, which identifies stress fractures and early changes. Therefore, where there is clinical suspicion of a femoral neck stress fracture and initial radiographs appear normal, referral to an orthopaedic surgeon should be made early.

Features suggestive of a stress fracture on subsequent x-rays may include linear lucency or cortical changes – both AP pelvis and lateral hip views should be obtained.

Treatment and management

Management of femoral neck stress fractures is predominantly non-operative, comprising provision of crutches, and a period of non-weightbearing and activity restriction.

However, those who sustain a displacement of the stress fracture will require surgical intervention (either fixation or replacement, dependent on the presence of avascular necrosis), and where there are large stress fractures on the tensile side or fatigue lines >50% of the width of the femoral neck, fixation with cannulated screws may also be indicated.

To help prevent the consequences discussed following diagnosis, patients should be followed-up regularly to be monitored for fracture displacement.

Hip pain: cartilage tears

Causes

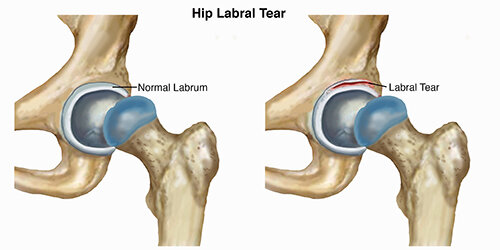

Athletes who participate in repetitive twisting or pivoting activities – such as hockey, football or long-distance running – can be at risk of developing a tear in the labrum, the cartilage which lines the rim of the hip joint. The chances of this are increased in individuals who also have underlying structural abnormalities, such as femoro-acetabular impingement, and of course such tears can also be traumatic (sustained during injury to, or dislocation of, the hip joint).

Tear of the labrum (Pro Dynamic Physical Therapy Inc.)

Clinical indications

Although many labral tears are asymptomatic, some can be debilitating and can limit range of movement and participation in running and other activities. There are often complaints of pain or stiffness in the hip, groin, buttocks or radiating to the knee, a reduced range of movement at the hip joint and sensations of clicking, locking or catching in the joint itself.

Diagnosis

Although x-rays can be useful initially to identify pre-existing structural abnormalities or concurrent bony injuries, the labrum itself can only be visualised on MRI.

Labral tears are best visualised by a specialised type of MRI known as an MR arthrogram, during which radio-opaque dye is injected into the hip joint and the images examined for evidence of leaking of this dye through a potential tear. However, the introduction of 3T MRI scanners, which are more detailed, may allow tears to be visualised without the need for invasive dye injection and the potential for adverse reactions.

Treatment and management

If you suspect a labral tear, it is recommended that you see an orthopaedic hip specialist – ideally one specialising in young adult hip problems – early.

Treatment options vary with symptom severity. Some recover well with a few weeks’ conservative management, whilst others will require open or arthroscopic surgery to repair or remove the torn piece of cartilage. A course of targeted physiotherapy to: strengthen the surrounding muscles; increase range of motion at the hip joint; and analyse movements in order to retrain movements and offload the hip, can often go a long way to alleviate the symptoms associated with labral tears.

Again, corticosteroid injections directly into the hip joint – usually performed under image-guidance by hip surgeons or radiologists – may be useful in providing some relief, and can also play a diagnostic role in localising the problem to the hip joint itself, as opposed to the surrounding soft tissues.

Injection of hyaluronic acid into the hip joint can also help with symptoms. Hyaluronic acid treatment is also known as viscosupplementation, and the substance is naturally found in human joints. It is an essential lubricant and shock absorber for the hip as it is our largest weightbearing joint.

Hip arthroscopy

The results of the recent UK FASHIoN Trial – a large, multi-centre, assessor-blinded randomised control trial comparing hip arthroscopy to conservative management (personalised, progressive, supervised hip physiotherapy) in patients with hip impingement support both management options in improving patients’ quality of life, but found hip arthroscopy to be superior in achieving clinical improvement (The Lancet, 2018).

Specifically for runners, the wider literature currently supports a moderately high midterm return-to-running rate for patients undergoing hip arthroscopy, as well as high patient-reported outcomes and a low complication rate (Chen et al, 2019).

Should patients opt for non-operative management or continue to train unaware of their labral tear, there is a risk that they could develop hip osteoarthritis due to the loss of the protective function and stabilisation provided by the labrum.

Non-operative

Should you develop early-onset degenerative changes secondary to an untreated labral tear, you should – in addition to their physiotherapy and input from other specialists – be referred on to a hip specialist orthopaedic consultant for assessment of further management.

Options may include injection therapy (corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, stem-cells – although more common in treatment knee osteoarthritis – or PRP, as discussed above) or joint replacement surgery once you reach a symptomatic threshold.

Oryon Imaging

We offer affordable, efficient diagnostic imaging (MRI from £275, x-ray from £70, ultrasound from £295 and DEXA at £115) in London’s world-renowned Harley Street medical district. Book a scan with us today.

About the author

Mr Arjuna Imbuldeniya

ICE Ortho Hip and Knee Clinic, West London

Tel: 02078594016 / 07784141294

Email: info@iceortho.com

Clinic locations:

The London Clinic (5 Devonshire Place, Marylebone W1G 6HL; 02037970297)

HCA Lister Hospital (Chelsea Bridge Road, London SW1W 8RH; 02039933046)

HCA Chiswick Clinic (Bond House, 347-353 Chiswick High Road, London W4 4HS; 02070316125)

BMI Syon Clinic (941 Great West Road, Brentford TW8 9DU; 02033148413)

Share this article

Most Recent

Posted on Thu Jul 3, 2025

How Long Does A Shoulder MRI Take?

Posted on Thu Jul 3, 2025

Posted on Tue Jul 1, 2025

Stay up to date

If you’re interested in keeping up with what we’re doing, just leave your email address here and we’ll send you periodic newsletters and other updates.